Yearbook 2010

Burma. Throughout the year, all attention was directed to the general elections promised by the military junta after pushing through a new constitution in 2008, which would make the country appear democratic. In March, a new electoral law was passed, according to which the military junta would hand-pick members of an electoral commission. The law also stipulated that punished persons may not be members of political parties. The wording was considered directly aimed at opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who has spent most of the last 20 years under house arrest. Election Law also prohibited members of religious orders from running for candidacy. This was intended to prevent Buddhist monks, the leaders of recent years’ protests against the junta, from entering politics.

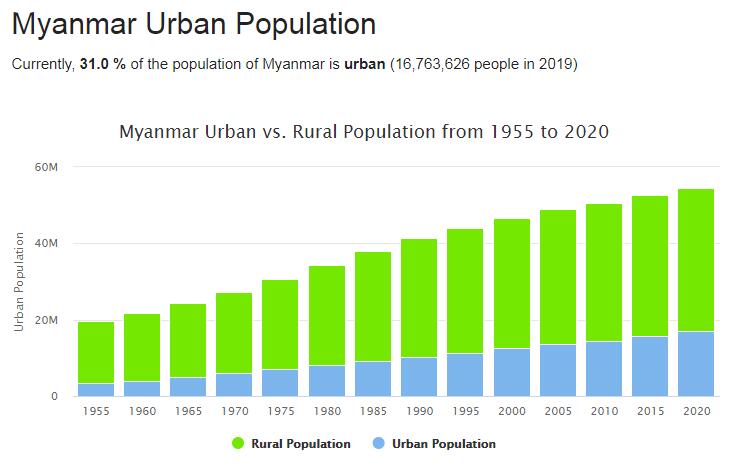

According to COUNTRYAAH, Myanmar has a population of 53.71 million (2018). About 20 ministers headed by Prime Minister Thein Sein left the military in April and formed the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which was the old junta-controlled “mass movement” USDA in new form. Aung San Suu Kyi’s party National Democratic Alliance (NLD), which had decided to boycott the election, dissolved on orders by the junta in May because it had not registered. A number of members then left the party and decided to stand for election under the name National Democratic Force (NDF).

- Abbreviation Finder: Check to see how the two letter abbreviation of BM stands for the country of Myanmar in geography.

Since the new constitution already guaranteed the military 25 percent of parliamentary seats and “former” military formed a party with superior resources, the election results were in practice clearly in advance. Any opposition MPs would not have the opportunity to push through amendments to the constitution of the junta, since such changes require more than 75 percent majority. Most countries condemned the election; it was largely only the important trading partner China that urged the outside world to support the process in Burma.

Before the election, the junta announced that no foreign observers or reporters would be admitted. The days surrounding the election broke Internet traffic in Burma, which was first interpreted as a cyber attack similar to those that had previously hit Estonia and Georgia. However, judges rather believed that it was the junta itself that blocked the web to prevent Burmese bloggers and photographers from informing the outside world.

Shortly before the election, it was also announced that the country’s official name was changed from Union Myanmar to Republic of Myanmar. According to softwareleverage, Burma also received a new national anthem and a new flag: a large white star against a background of three horizontal fields in yellow, green and red.

Shortly after the election, Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest, according to information without special conditions. She was able to hold public speeches immediately and start consulting on the future with her party mates. She struck a conciliatory tone and declared herself ready for a dialogue with the government. Her youngest son Kim Aris also got an entry permit and was able to meet his mother for the first time in ten years.

During the election day, the opposition complained of gross cheating and pressure on voters. When the election results were announced, USDP was presented as superior victor in both parliament’s chambers with over 75 percent of the vote. The junta-friendly National Unity Party (NUP), formed before the 1990 elections, and a party representing the Shan people became roughly equal. The NDF received eight seats in the lower house, the People’s Assembly.

November

Asian countries form record trade cooperation

November 15

Fifteen countries in Asia and the Pacific region sign the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) trade agreement. The members are some of the world’s largest economies: China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the ten Southeast Asian Asian countries. Together, they account for almost a third of the world’s total GDP. The cooperation needs to be ratified by nine countries, of which six are ASEAN members, in order to enter into force. India participated for a long time in the negotiations, but chose to withdraw in 2019 due to concerns about the consequences for domestic production. The United States stands outside the RCEP, which has been seen as a Chinese response to the major US trade initiative TPP, which when Washington withdrew from 2017 was renamed the CPTPP.

The NLD wins its own majority

November 8

Aung San Suu Kyi’s ruling NLD wins the parliamentary elections by such a large margin that it gets over 50 percent of the seats in the Legislative Assembly – even when the mandates reserved for the military are included. It shows the election authority’s official end result. The military-backed opposition party (USDP) claims electoral fraud and human rights groups criticize the failure to hold elections in certain conflict-affected areas. The respected think tank International Crisis Group (ICG) says, however, that even if irregularities turn out to have occurred, the NLD’s victory is so great that these would not change the outcome of the election. Of the 498 eligible seats in the two chambers, 22 will be vacant as elections cannot be held in these constituencies due to the security situation. Among the Burmese majority people, the NLD won an almost total victory, but even in the areas dominated by ethnic minorities, more people than expected voted for the NLD. The parties of the ethnic minorities had mixed results, but they did not go as far as many observers thought.

Flying Buddhist monk gives up

November 2

The ultra-nationalist and anti-Islamic Buddhist monk Ashin Wirathu surrenders to the police after fleeing after an arrest warrant was issued against him for hate crimes 18 months earlier. Ashin Wirathu has been particularly hard on the Rohingya, but it was when he accused Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD government of corruption that he was indicted. Many observers believe that Ashin Wirathu is trying to influence the outcome of the election on November 8 by giving up six days before election day. In the media, he urges Burmese to vote out Suu Kyi and the NLD. The monk risks several years in prison if he is convicted of libel or hate crime.