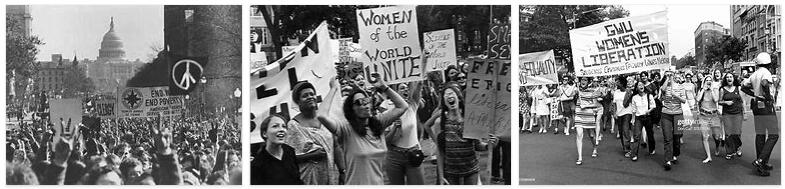

The problems that emerged in the last period of the Eisenhower administration had placed the USA in front of the urgency of new political choices. The alternation of coexistential openings and sudden stiffening characterized Khrushchev’s international action; on the other hand, the rate of increase in national income was modest both with respect to the growth of the Soviet economy in the 1950s, and with respect to the “economic miracles” of the Euro-Western countries. The need to get out of the conditions of a balance guaranteed by armaments, therefore, met with the need to face the crisis of employment and to give new impetus to the productive apparatus. JF Kennedy’s three-year period, from January 1961 to November 1963, he opposed the Eisenhower period for a style change in the White House. While Eisenhower had chosen his aides from among the great industrialists and businessmen, Kennedy’s advisers were recruited by preference from intellectuals and university professors: thus Defense Minister RS MacNamara, Councilor G. Bundy, Minister of Justice R. Kennedy, brother of the president. Vast expectations of renewal were raised by the “New Frontier” program: fighting poverty and racial discrimination, helping underdeveloped peoples. The country was brought out of the economic recession that had marked the final years of the Eisenhower presidency. Kennedy won the game against the steel magnates who wanted to raise prices; he moved cautiously to restart the economy, increasing federal government spending, expanding foreign trade, and achieving an increase in domestic production without a corresponding increase in prices. But unemployment continued to exceed 5% of the global workforce. Foreign policy, on the other hand, continued to be inspired by the principle of “containment” of the communist expansion in the world. Kennedy met with the failure of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba (when, in April 1961, a group of exiles tried with the help of the American services to establish a bridgehead on the island to overthrow the revolutionary regime) and assumed the responsibility for the direct American involvement in Vietnam. In South America the president became champion of Alliance for Progress, an ambitious reconstruction plan accepted at the Punta del Este (Uruguay) conference in August 1961, when the USA made a commitment to disburse $ 20 billion over a decade for this purpose; on the other hand, he wanted the expulsion of the Castro regime from the Organization of American States and put in place a rigid boycott, which ended up bringing Cuba even closer to the Soviet Union. The popularity acquired by the Alliance for Progress was ultimately compromised by the developments of the Cuban crisis which brought tension with the USSR to its peak in December 1962 and ended with the withdrawal of Soviet missile installations on the island. On that occasion the American government excluded both the armed invasion of Cuba and the aerial bombardment of the ramps, choosing instead the “quarantine”, that is the naval blockade of the island, and leaving Khrushchev time to reflect and retrace his steps. Soviet ships carrying missile material to Cuba avoided collision with the American fleet, and turned back. The first Soviet secretary, who had probably been motivated by the intention of gaining positions in Cuba to obtain concessions on the German question, ended up agreeing to the removal of the missiles, requested by Kennedy.

In the European sector, Khrushchev’s reopening of the Berlin problem had highlighted a variety of attitudes within the Atlantic Pact countries: faced with the intransigence of the Bonn government, supported by de Gaulle, American diplomacy had shown willing to enter into negotiations and had had to accept the fait accompli of the barrier erected in the former German capital in August 1961. The first concrete fruit of the détente was only grasped in August 1963, when an agreement was signed in Moscow for the partial suspension of nuclear experiments (see atomic, non-proliferation, in this App.). But shortly after the young president’s life was cut short by the assassination of Dallas, which aroused deep emotion throughout the world, bringing a blow to the open coexistential expectations, with different ways and objectives, by the exceptional personalities of Khrushchev, John XXIII and by Kennedy himself. Even after the publication of the voluminous report of the commission of inquiry chaired by Judge E. Warren, which attributed the crime to a single individual, many doubts remained about a possible plot with the participation of other elements.

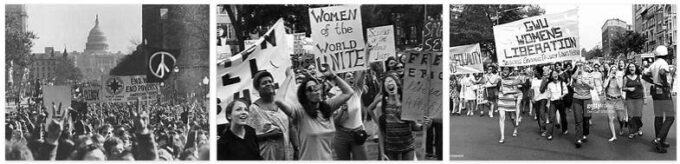

The Negro question took particular prominence during Kennedy’s presidency. Since 1954 the Supreme Court presided over by the liberal Warren had given impetus, with the famous decision in the Brown case, to the movement for desegregation in schools. During the Kennedy years there were initiatives of wide resonance thanks to the activity of the NAACP (the Association for the Advancement of Black People, chaired by the skilled M. Evers), the courageous non-violent campaign led by the black Protestant pastor Martin Luther King and the cooperation of several white volunteers. These were years of great hopes, but marked by violent resistance from southern racists. There is no doubt about the sympathies of the President and his brother Robert, Minister of Justice, for the Negro cause. But Kennedy had to act with caution so as not to compromise other points of his program intended for the development of the Southern states: so it must be said that the progress made by the Negroes was due more to their growing strength and organization than to the good will of the liberals. By winning even violent opposition from racists, i Freedom riders, whites and associated negroes, occupied the seats reserved for whites in means of transport, in bars, in gas stations, in motels. The struggles for civil rights, with the cooperation of whites, were among the most significant phenomena of those years. The Freedom riders movementwas encouraged by the Supreme Court decision of May 14, 1961 regarding desegregation in bus stations. In Montgomery, where the white mob had occupied a bus station, the federal government had to send hundreds of armed men to restore order. In Mississippi, racists resorted to hundreds of arrests, using that state’s police. But the Ministry of Justice was successful in the struggle for desegregation in a good number of airports and stations. Notable successes were also had in the campaign to lift the restrictions on the voting rights of blacks and to persuade them to register on the electoral roll. In Mississippi there was a clash between racists and the federal government when the Negro J. Meredith, a war veteran, wanted to enroll at the University of Mississippi. State Governor Ross Barnett opposed federal court decisions, but Kennedy responded by sending about thirty thousand army men and putting the National Guard under control. One night of terror, with two dead and hundreds injured, was the price paid for Negro Meredith to attend college, protected by federal agents. On Good Friday 1963 ML King led a massive demonstration, troubled by serious incidents, in Birmingham, Alabama, believed to be the main bastion of white supremacy. Alabama governor G. Wallace also opposed the admission of blacks to his state university; but he had to give up when Kennedy put the National Guard under federal control. When M. Evers fell victim to an attack, Kennedy stressed the gravity of the Negro question and asked Congress to pass the largest civil rights law in the history of the country, which only his successor was able to carry out.On August 28, 1963, the president spoke to a crowd of two hundred thousand people., which met in Washington to express enthusiastic approval of the bill. But in Birmingham in September, a bomb killed four black children in a church.

His successor, the Texan LB Johnson, vice president, who had made his first trials as a follower of F. Roosevelt and a young official in Texas during the New Deal years, gifted with great skill in the committees of the Congress, in the first months of his mandate he achieved notable successes in domestic politics. In February 1964, he succeeded in getting Congress to approve a tax cut of over 10 billion dollars, thus favoring a significant increase in global national production and in the purchasing power of consumers. The average for the poor in the country was reduced from 22% to 11%. Even a conservative economist like M. Friedman claimed to have converted to Keynesian theories. But studies by M. Harrington and others showed that a fifth of the nation, mostly Negroes but also whites from the Appalachian Mountains, still had a very low standard of living compared to the prosperity of the rest of the population. A series of laws of 1964-65 provided aid to schools of all grades and served to offer jobs, especially in the poorest areas of the country. Johnson launched the slogan of “Big Society”, where the quality of life would be improved for all through education; and when the Republican party chose a reactionary such as Senator B. Goldwater as its candidate for the 1964 presidential election, he defeated him by getting more than 60% of the national vote and winning in all states except Arizona and the five state of the South where racist voters prevailed. The majority that Johnson already enjoyed in the two Houses was also significantly increased, giving hope that the conservative elements of the two parties could no longer block political and social reforms. Fair Deal by HS Truman, such as medical assistance for the elderly and grants for elementary and middle school children belonging to poor families. Ecological measures were adopted and subsidies were allocated for those who could not afford housing costs. In essence, thanks to such social measures, the early years of Johnson’s presidency rivaled those of the New Deal.

However, the inflationary process already underway was accentuated by the growing commitment to Vietnam, which also produced a moral split in the country, which was difficult to remedy, and alienated large sections of world opinion from the USA. Johnson refused the advice of the extremist “hawks” who asked him to use the atomic weapon, but the techniques then adopted were almost as destructive, from carpet bombing with incendiary bombs, to the destruction of countless villages, to acts of cruelty against guerrillas. and civilian populations who protected them. Johnson made use of a two-House resolution, the Tonkin resolution, based on the attack by North Vietnamese units on US warships procuring information for the use of South Vietnamese (it is not clear whether the incident had been caused by American leaders) to have hands free as head of the armed forces for operations in southern Vietnam. Johnson wanted to apply the containment policy also in South-East Asia, without distinguishing between geographically very different areas: he did not take into account the changed world situation, the contrast between Russia and China, the necessary distinction to be made between vital and non-vital areas. for the security of the United States. He understood only that the “imperial republic” (in the expression of R. Aron) could not and should not yield to Vietnam; thus the number of American troops commanded by General W. Ch. Westmoreland in Southeast Asia gradually increased until it reached the figure of half a million men in addition to the fleet and the aviation. The Vietnam War proved costly in human lives (several tens of thousands of deaths) and in money, the most expensive since the Second World War. The commitment in Southeast Asia also had negative repercussions in other sectors: in South America the plan of the Alliance for progress fell, in Brazil a military dictatorship asserted itself with the apparent lack of American interest, in the Dominican Republic the marines they intervened to prevent a progressive government from coming to power. Public opinion polls showed that the president and the hawks had the consent of the majority of the country; and yet the most progressive, university youth, intellectuals and even 20 authoritative senators like JW Fulbright contested the abuse of presidential powers over Congress, and demanded that the American intervention be stopped. There were riots in the universities; large numbers of young people escaped military obligations by taking refuge in Canada and elsewhere. But what finally persuaded Johnson to change course was the success of North Vietnamese General Giap in the Tet offensive in early 1968, which led to the occupation of many South Vietnamese strongholds and threatened Saigon itself. After taking command of General Westmoreland on March 21, in a dramatic speech on television, Johnson declared that he would not reappear the candidacy in the upcoming presidential elections, and announced that he would limit the aerial bombardments only to the southern areas of Vietnam, entrusting to the Saigon troops the major responsibilities of the war to allow for a gradual withdrawal of US troops. WA Harriman soon went to Paris to start talks with North Vietnamese representatives, but without immediate results. The Vietnam War caused riots in a large number of high schools. A good number of liberal professors sympathized with the students, but in some places, as at Cornell and Columbia universities, there was police intervention and even bloodshed. Students objected to traditional curricula and teachers. This revolt against secular cultural traditions revealed, as in Europe, a good dose of improvisation, superficiality and spontaneism; but in opposition to the American commitment to Vietnam, which was deemed unfair, intellectuals such as AN Chomsky and PM Sweezy found themselves alongside the students. Several years earlier, an economist like JK Galbraith had contrasted the model of the “affluent society”, based on consumerism, with a different type of economy based on planning and the precedence of investments of social utility. Students objected to traditional curricula and teachers. This revolt against secular cultural traditions revealed, as in Europe, a good dose of improvisation, superficiality and spontaneism; but in opposition to the American commitment to Vietnam, which was deemed unfair, intellectuals such as AN Chomsky and PM Sweezy found themselves alongside the students. Several years earlier, an economist like JK Galbraith had contrasted the model of the “affluent society”, based on consumerism, with a different type of economy based on planning and the precedence of investments of social utility. Students objected to traditional curricula and teachers. This revolt against secular cultural traditions revealed, as in Europe, a good dose of improvisation, superficiality and spontaneism; but in opposition to the American commitment to Vietnam, which was deemed unfair, intellectuals such as AN Chomsky and PM Sweezy found themselves alongside the students. Several years earlier, an economist like JK Galbraith had contrasted the model of the “affluent society”, based on consumerism, with a different type of economy based on planning and the precedence of investments of social utility. superficiality and spontaneism; but in opposition to the American commitment to Vietnam, which was deemed unfair, intellectuals such as AN Chomsky and PM Sweezy found themselves alongside the students. Several years earlier, an economist like JK Galbraith had contrasted the model of the “affluent society”, based on consumerism, with a different type of economy based on planning and the precedence of investments of social utility. superficiality and spontaneism; but in opposition to the American commitment to Vietnam, which was deemed unfair, intellectuals such as AN Chomsky and PM Sweezy found themselves alongside the students. Several years earlier, an economist like JK Galbraith had contrasted the model of the “affluent society”, based on consumerism, with a different type of economy based on planning and the precedence of investments of social utility.

In July 1964, overcoming the obstruction of the racists of the two parties, Johnson managed to get E. Mck approved, with the help of HH Humphrey. Dirksen and others, that vast civil rights bill that Kennedy had failed to deliver. Discrimination in hotels, motels was outlawed, restaurants, gas stations, stadiums and swimming pools; federal subsidies were denied to schools and hospitals that practiced discrimination. Regarding the registration of blacks on the electoral roll, which was hindered by racists through so-called culture tests, it was established that the attendance of six years of elementary school was sufficient to exercise the right to vote. However, not even this law was able to heal the scourge of discrimination. ML King was imprisoned in a racist county in Alabama; when Governor GC Wallace wanted to organize a demonstration in the state capital, Montgomery, he allowed the police to attack the demonstrators. The president had to intervene, putting the Alabama National Guard under the control of the federal government. With the protection of federal officials, the number of blacks enrolling on the electoral roll increased considerably in Mississippi and Alabama; meanwhile the Supreme Court declared the payment of the tax to exercise the right to vote unconstitutional, while the number of blacks holding public office in local and state assemblies increased considerably. Barring sporadic riots, the civil rights movement seemed to have progressed sufficiently to ensure the peaceful advancement of Negroes in American society when the severe riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles in August 1964 brought down all illusions. The racial riots which in four consecutive summers starting in 1964 desolated a number of American centers from Los Angeles to Newark, from Chicago to Detroit, have multiple causes. It was surprising that they exploded in centers where the conditions of the negroes were comparatively not the worst; the struggle for civil rights had yielded remarkable results, but the implementation of the laws met with resistance while the resentments accumulated over the decades required immediate solutions. The unbridled television advertising highlighted the unnecessary consumption of the middle class (30% of the population had incomes above 10,000 dollars a year), from which the black population crowded in the ghettos of the industrial cities was still excluded. The rapid decolonization in the countries of Asia and Africa, the rise of new independent states, gave the Negroes the awareness that they were not an isolated minority in the world. Faced with the disorientation of the integrationist liberals and the black majority itself, exasperated minorities sought the path of violence. In July 1967, the Newark riots, which lasted five days, left 26 dead and 1,200 injured; in Detroit, where the Negro population also enjoyed better economic conditions than in other regions, 43 dead, over 200 injured and thousands of fires were reported. While in previous years there was a tendency of Negroes towards integration, leaders such as S. Carmichael began to spread, in contrast to ML King’s non-violent campaign, the slogan of ” black power “: instead of the campaign for civil rights sponsored by white liberals, blacks they should have waged their own specific battle, exercising the right to vote to seize some local administrations and resorting to boycott to hit certain economic interests; but above all they should have become aware of their race, developing a distinct culture opposed to that of the whites.

The “Muslim Negro” movement claimed the birth, in US territory, of a state inhabited and ruled exclusively by Negroes; it had its prophets in E. Muhammad and Malcolm Little (who passing to Islam took, repudiating the name imposed on his ancestors by the white masters, the new name of Malcom X, under which he published an important and successful autobiography), later divided by a rivalry that was ended only by the violent death of Malcom X. From the extreme wing of the Black Power movement originated the group of ” Black Panthers ” (Black panthers), who preached the use of direct action, the burning of the temples of consumerism and looting. The strategy of non-violence was devalued by new tragic events: J. Meredith, who had led a non-violent march in Mississippi, was attacked and wounded; and on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King himself was murdered by a white racist in Memphis, Tennessee.

The 1968 presidential elections took on particular importance. The increasingly determined opposition of intellectuals and students, racial unrest, rising inflation were all problems that Johnson left unsolved. In the first months of the year, Senator E. Mac Carthy of Minnesota introduced himself and affirmed in various states that for his rapid peace program in Vietnam and for his personality as an idealistic intellectual he won the competition of tens of thousands of young people enthusiastic and seemed to endanger Vice President H. Humphrey, Democratic candidate. His affirmation later turned out to be a flash in the pan, when R. Kennedy entered the competition, enjoying even more enthusiastic acclaim and successes in the primaries of various states. But the race for candidacy was cut short by another crime: the former president’s brother was also murdered in Los Angeles by a young Jordanian emigrant. Humphrey’s position was also threatened on the right by the assertion, especially in the southern states, of the governor of Alabama G. Wallace, who came up with a clearly racist agenda. After the racial unrest that wreaked havoc in the ranks of the integrationist liberals, there had been a wave of ebb in the country (white backlash) in large sections of the population, not excluding the workers who had achieved wealth and other elements of the middle class, convinced that the blacks had obtained too many concessions that ended up weighing heavily on the federal and state budgets. The coalition, which has lasted since the time of Roosevelt and the New Deal, among workers, negroes and poor whites it seemed to have to crack. But the election results showed that the breakdown had been less than expected. In the Republican field, after the defeats against Kennedy, in 1960, and then in the race for the governorship of California, R. Nixon seemed a politically finished man; but in 1966 he had made an astonishing recovery, showing his political and organizational prowess in the service of his party, which had won back quite a few seats in Congress. Then, in the 1968 electoral competition, Nixon was able to assert himself against his rivals, including the ultra-conservative R. Reagan governor of California, and to win the presidential candidacy. Introduced himself as Eisenhower’s heir, he promised to heal the rifts and conflicts in the country and to liquidate the war in Vietnam. He appealed to the “silent majority” who had disapproved of the excesses of the Negroes and the various avant-gardes and who, after supporting Johnson’s policy in Southeast Asia, demanded that America emerge from the unfortunate Vietnamese adventure without losing face. The Democratic Chicago convention that appointed Humphrey was marked by inordinate police violence against left-wing opponents, while the Republican one in Miami took place in sleepy calm. Humphrey was hampered in his campaign not only by the initial success of rivals Mac Carthy and Kennedy, but by the acclaim garnered by racist G. Wallace in the South and elsewhere. He had collaborated with Johnson and could not break away from the president, proclaiming himself an advocate of peace; liberal in domestic politics, he did not enjoy the confidence of the pacifists. It came out very badly from the primary, but had a surprising recovery in the last weeks leading up to the election, when, finally breaking away from Johnson, he declared his determination to end hostilities. Nixon won over Humphrey, but by a very narrow margin of the popular vote, less than thei %, although the victory in the constituency was 301 votes to 191. Wallace won in five states, all in the South, collecting just under 10 million votes. The Democrats retained a majority in the two Houses of Congress. Analyzing the electoral results it was seen that the traditional Rooseveltian majority in the Democratic party, although diminished, still held up. The narrow margins of electoral success and the existence of a Democratic majority in Congress forced Nixon to act with extreme caution. According to some advisers, his model was to be Disraeli’s policy in England of ” Tory democracy.”still in 1972 this plan had not been approved; moreover, the elections to the Congress, held in that same year, did not change the composition of the two Houses. There were some positive facts in the ecological field, but Nixon’s policy failed in dealing with inflation. The cost of the war in Vietnam presented two alternatives; to allow inflation to continue, or to try to curb it at the cost of seeing rising unemployment. Over the “income policy” suggested by some economists, Nixon preferred cuts in the federal budget and monetary restrictions on the part of the issuing bank; but the rise in interest rates put investors in difficulty and there were sharp falls in listed securities, to which were added failures, even sensational ones. The global production index, tax revenue declined and unemployment reached 6% by the end of 1970, while prices continued to rise. Appointed AE Burns to the presidency of the Federal Reserve, Nixon appeared to convert to a moderate Keynesian line; but even this did not give sufficient results as prices and unemployment continued to rise in 1971 and, for the first time in eighty years, US imports outstripped exports. Then there was another sharp turn, hopes the new Treasury Minister J. Connally. On August 15, 1971, Nixon announced the freezing of wages, prices and rents for ninety days; it required lower taxes to stimulate business, imposed a surcharge on many important products, and paved the way for a devaluation of the dollar. Thus he denied his original economic policy amid the protests of the workers and liberal groups, who noted that the fixed income categories were affected by the crisis, while profits and dividends were not affected. At the same time, the president, to remedy the deficit in the trade balance, announced “temporary” tariffs on imports and measures equivalent to a real devaluation of the dollar, causing serious alarm in Europe and Japan. It took July 1972 before there was an increase in national production and a fall in prices. to remedy the deficit in the trade balance, it announced “temporary” import duties and measures equivalent to a real depreciation of the dollar, causing serious alarm in Europe and Japan. It took July 1972 before there was an increase in national production and a fall in prices. to remedy the deficit in the trade balance, it announced “temporary” import duties and measures equivalent to a real depreciation of the dollar, causing serious alarm in Europe and Japan. It took July 1972 before there was an increase in national production and a fall in prices.

Nixon was more fortunate in foreign policy, showing considerable elasticity also due to the influence of H. Kissinger, presidential adviser for foreign policy and later foreign minister. Nixon’s visits to China and the Soviet Union marked a turning point in the politics of a man who in the past had characterized himself as an uncompromising anti-Communist. In July 1971 the State Department announced that the USA would no longer oppose the entry of People’s Republic of China into the UN, which it did shortly thereafter; great publicity was given to Nixon’s visit to Beijing in February 1972, which served to improve relations between the two countries, even if it did not yield substantial immediate results. In May of the same year Nixon went to Moscow: following this visit, an agreement was reached to improve access to Berlin. Negotiations for the limitation of strategic armaments continued with the Russians, freezing the equilibrium achieved and giving up on both sides the costly projects to build defensive systems against possible nuclear attacks. The liquidation of the Vietnam war proved much longer and more difficult than expected. Nixon had promised the gradual withdrawal of the troops; there were over half a million men in Vietnam by the time he took office, and on the eve of his re-election in 1972 there were only a few tens of thousands of soldiers left in addition to the fleet and air force. But the Paris negotiations between Cabot Lodge and the North Vietnamese failed and a long pause followed before they were resumed by H. Kissinger. Nixon moved cautiously so as not to displease both “the hawks” and the “doves”. The massive bombings continued, and it has been calculated that more bombs were dropped in Vietnam during the entire conflict than not only that used in Korea, but even that against Nazi Germany. It must be said that, before the Cambodian (1970) and Laotian (1971) affair, the atmosphere of revolt that had marked the 1960s had considerably diminished. The economic recession forced students to worry about looking for a professional job, while the persuasion spread that the violent protest had become counterproductive and had caused a hardening in law enforcement and public opinion. L’ invasion of Cambodia caused the revolt to flare up again, as at the University of Kent in Ohio, where four students were killed and others injured by the public force. While still supported by the silent majority and the strata of wealthy workers, who, according to public opinion polls, also showed support for the initiative to undermine the port of Haiphong, Nixon’s policy alarmed liberal and pacifist elements. On the advice of the increasingly influential Kissinger, Nixon announced that he wanted to promote the “Vietnamization” of the conflict. It was a question of enabling the South Vietnamese forces, armed and equipped by the USA, to resist those of North Vietnam while providing for a gradual repatriation of American troops. Meanwhile, the conflict had cost another 15,000 soldiers perished in the rice fields of Vietnam. Conversations in Paris were progressing slowly, although, on the eve of the 1972 presidential election, Nixon announced that peace was in sight. Conversely, the landing of the first astronauts on the moon, on July 16, 1969, had produced an enormous impression: the results of the fabulous investments in the space program had been grasped, which had already begun under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, reaching and overcoming the Soviets who they were assured a head start in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. 000 soldiers perished in the rice fields of Vietnam. Conversations in Paris were progressing slowly, although, on the eve of the 1972 presidential election, Nixon announced that peace was in sight. Conversely, the landing of the first astronauts on the moon, on July 16, 1969, had produced an enormous impression: the results of the fabulous investments in the space program had been grasped, which had already begun under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, reaching and overcoming the Soviets who they were assured a head start in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. 000 soldiers perished in the rice fields of Vietnam. Conversations in Paris were progressing slowly, although, on the eve of the 1972 presidential election, Nixon announced that peace was in sight. Conversely, the landing of the first astronauts on the moon, on July 16, 1969, had produced an enormous impression: the results of the fabulous investments in the space program had been grasped, which had already begun under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, reaching and overcoming the Soviets who they were assured a head start in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. on the eve of the 1972 presidential election, Nixon announced that peace was in sight. Conversely, the landing of the first astronauts on the moon, on July 16, 1969, had produced an enormous impression: the results of the fabulous investments in the space program had been grasped, which had already begun under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, reaching and overcoming the Soviets who they were assured a head start in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. on the eve of the 1972 presidential election, Nixon announced that peace was in sight. Conversely, the landing of the first astronauts on the moon, on July 16, 1969, had produced an enormous impression: the results of the fabulous investments in the space program had been grasped, which had already begun under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, reaching and overcoming the Soviets who they were assured a head start in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. the results of the fabulous investments in the space program, which began under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, had been reaped, reaching and surpassing the Soviets who had secured an advantage in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers. the results of the fabulous investments in the space program, which began under Kennedy and continued under Johnson, had been reaped, reaching and surpassing the Soviets who had secured an advantage in the Eisenhower years. In the chorus of cheering voices there was no lack of notes of dissent from those, scientists and experts, who saw in the sensational enterprise another stage in the atomic arms race between the two superpowers.

The plan to help poor families set the pace. What was done on the subject of school desegregation was due more to the previous decisions of the Supreme Court and the initiatives of the Johnson government, than to the will of Nixon and his government. Although an investigation showed the economic progress made by the Negroes, the view emerged among the poor strata that the Nixon government tended to be the most contrary to their interests from Eisenhower’s time onwards. And indeed, in a speech of his that alarmed the liberals, Nixon did not hesitate to say that he was in an intermediate position between the integrationists and the segregationists: the presidential elections of 1972 were approaching and Nixon had to try to widen his electoral base in the states. of the South, stealing votes from the future racist candidate Wallace. Justice Minister JN Mitchell, who represented the conservative interests of the big Wall Street corporations, convinced Nixon that the secret to winning the 1972 election was betting on the votes of Southern racists and the numerous “silent majority” members. neglecting the liberal and progressive elements who viewed his government with growing skepticism and aversion. Despite Kissinger’s activism, the Paris negotiations were taking a long time. The killing of some students in Kent signaled a wave of unrest in numerous university colleges and peaceful demonstrations, culminating in a convergent march on Washington. Comforted by public opinion polls, according to whom far too many concessions had been made to blacks, Nixon hesitated to encourage school integration by transporting black children to schools by public transport; but he was called to the observance of the law by a decision of the Supreme Court, which reaffirmed the integrationist policy. Nixon found himself replacing the president of the Supreme Court by age, and in place of the liberal Warren he appointed the moderate WE Burger. There were four more posts to fill, and he tried the shot of forming a decidedly conservative court to please the southern electorate; but twice the names he proposed were rejected by the Senate. It was a setback for the president, who had to settle for other less hated candidates in Congress for conservatism or incompetence. During the election campaign Nixon was benefited by various circumstances. Democratic reactionary candidate Wallace, who had reaped great success in the primary, was seriously injured and had to retire from the race. Precisely to oppose Wallace’s extremist theses, in the Miami convention the Democratic delegates, including many young people who were voting for the first time, chose as candidate G. MacGovern of South Dakota, a progressive intellectual with an immediate peace program in the Vietnam and extensive social reforms. But he displeased the Democratic electorate over some strange proposals, one in particular that was later abandoned, namely the government gift of a thousand dollars to every single American from the poorest to Rockefeller; moreover its language in the the Vietnam affair appeared excessively defeatist to those of the Democrats who had supported Johnson’s policy. Not a few, therefore, of the votes that had gone to Humphrey in 1968 shifted, for lack of better prospects, to the incumbent president. Moreover, a week before the elections, he had Kissinger announce that peace in Vietnam was in sight. A news story, which would later take on quite other dimensions, had little immediate relevance in the clamor of the electoral campaign; elements of the pro-racist “mafia” had forced entry into the headquarters of the Democratic party, housed in the building called Watergate, to set up microphones and thus obtain information on the opponent’s strategy. Nixon’s apparently sensational victory it was actually limited by various negative elements: participation in the polls was very low, since many voters did not know which one to prefer between the two candidates; the majority in the two chambers remained with the Democrats, who actually won two more seats in the Senate. Nixon won in all states except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, the seat of the federal government, mostly black; he had 521 votes from the constituency, against 17 for Mac Govern, and 45.9 million for the popular vote against 28.4 for the competitor. The historic Rooseveltian majority had this time crumbled; the historically democratic “solid South” had passed to the Republicans, and multitudes of “blue collar”, that is, wealthy workers, had voted for Nixon. Faced with MacGovern’s extravagances during the electoral campaign, even G. Meany’s CIO-ALF union center, instead of suggesting support for the Democratic party, declared its neutrality in the electoral competition. Nixon seemed at the height of his fortune when the Watergate affair brought him very close to being indicted by Congress and forced him to resign (August 9, 1974).

In January 1973, after 19 months of negotiations, Kissinger and Le Duc Tho signed a ceasefire in Indochina. The event was hailed as “peace with honor”. In reality, the major world power had failed to overthrow the North Vietnamese and Vietcong, who would subsequently conquer the southern part of the country and establish a Communist dictatorship. Meanwhile, public opinion in the institutions was deeply shaken. In May, millions of Americans watched the Senate Committee of Inquiry sessions on television, which revealed a series of illegalities committed by senior government officials: the organized raid on Democratic headquarters, attempts to hide their responsibilities, and others. acts aimed at discrediting the men of the opposing party. Nixon tried to keep aloof, almost all of this having happened without his knowledge. But the direct executors denounced the principals in the circle of the president’s collaborators. In October there was a twist when Judge A. Cox refused to obey the president’s order to forgo the tapes on which Nixon’s own conversations with his closest associates were recorded. Nixon ordered thehisattorney general to sack Cox; but he too refused. Three senior officials who had resisted Nixon were fired. It was then that the House of Representatives decided to investigate whether there were sufficient grounds for indicting the president. At the same time, vice-president S. Agnew, a standard bearer of the “law and order” program, was forced to resign because he was accused of corruption and fraud against the tax authorities (he was replaced by G. Ford: 12 October 1973). Meanwhile, inflation worsened by the oil crisis, which caused the prices of fuel and many other products to rise. After painful hesitation, Nixon was persuaded to resign to avoid being impeached. The revelations surrounding the Watergate affair, including attempts to polluting the CIA and the FBI and involving the highest office of the state had created a wave of distrust in the institutions. Peace, despite Kissinger’s activism, proved to be anything but consolidated, both in Indochina and in the Middle East. Assuming the succession, Ford retained Kissinger in the foreign ministry and chose N. Rockefeller as vice president, whose appointment was approved not without a thorough preliminary investigation into his financial position and private life. The Congress had developed serious suspicions about the executive’s policy and was demanding a greater share in the direction of business: the life of the Ford government was not going to be easy in the face of a vigilant and riotous Congress.

After Nixon’s resignation, G. Ford’s succession as president was greeted with relief. But the truce between Congress and the presidency was broken following the pardon granted by Ford for all the crimes the former president may have committed, and the return to Nixon of the disputed documents and tapes: these acts were seen as an affront to the House Judicial Affairs Committee, which was preparing to impeach Nixon, and appeared to run counter to a measure, issued by Ford, of limited leniency to defectors in the Vietnam War. The presidential program to fight inflation relied more on citizen self-discipline than government measures; however, cuts were made in oil imports and a 5% surcharge was imposed on households whose incomes exceeded $ 15,000 annually. In the autumn of 1974 the recession worsened and in December unemployment reached 7%; mass layoffs in car factories followed, while the balance of payments was also affected by the high price of oil. The psychological aspects of the Watergate scandal were reflected in the 1974 congressional elections, in which the Democrats won 43 seats in the House, 3 seats in the Senate and 4 seats as governor; some of the more conservative Republicans were not re-elected. Congress intended to reaffirm its authority over the executive, increasing the powers of the Speaker of the Chamber and inflicting a blow to the principle of seniority in participation in legislative committees, as well as in the participation of the same people in different commissions. A law was also passed, in 1973, which gave the president ample powers to negotiate a reduction in customs tariffs with foreign countries; the measure had been delayed by the controversy over the granting of the most favored nation clause to the USSR, when this country limited the emigration of dissident elements, and especially of Jews who wanted to move to Israel. The approved bill made trade concessions to those socialist countries that did not restrict emigration. Détente with the USSR was strengthened, however, following the Vladivostok meeting (November 1974); Ford and Brežnev established the lines of a second SALT agreement (v.missile, in this App.), who nevertheless encountered serious obstacles, even after the replacement of the Minister of Defense JR Schlesinger (harshly critical of Kissinger’s policy of agreement, which he considered dangerous for the security of the USA). However, a five-year agreement was negotiated for the sale to the USSR of a quantity of grain between 6 and 8 million tons per year, correlating with the importation of oil from the Soviet Union itself. The main event of 1975 in foreign policy was the end of the war in Indochina, which lasted a decade. The war in South Vietnam ended on April 30, when the South Vietnamese government surrendered to the Communists and North Vietnamese troops entered Saigon; a few weeks earlier, Congress had rejected Ford’s proposal for military and “humanitarian” aid to South Vietnam to the tune of some $ 1 billion. In the Middle East, on the other hand, Kissinger had a success, negotiating as a mediator an agreement between Israel and Egypt: Israel withdrew its troops from a part of the Sinai peninsula, while American civilian personnel went there to ensure the execution of the established plan.. After the failure in Vietnam, Ford wanted to assure his allies at the NATO conference in Brussels that American power was intact. He returned to Europe in July 1975 to attend the Helsinki meeting, where representatives of 35 states signed the final act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, which sanctioned theEuropean security, in this App.). Ford also attended a conference of six major industrial countries in November to determine ways of securing economic recovery and reducing unemployment. Methods for achieving monetary stability and smoothing out the divergences between the USA, favorable to a continuation of exchange rate fluctuations, and France, which preferred to return to a system of fixed relations between the currencies of individual countries, were also discussed.

The new president JE Carter (v.), Of Baptist confession, exponent of rural America and first head of state from the “deep South”, had established himself in a segregationist environment as a champion of black rights; as governor of Georgia, he had implemented a program of reform, with the reduction of government offices and the introduction of a good number of blacks into the state bureaucracy. With populist veins he had insisted in his speeches on the importance of moral values, defeating the racist Wallace in Florida; on the republican side, the ultra-conservative Reagan had failed to assert himself against President Ford. Both Ford and Carter had made psychological mistakes in the presidential campaign: a, while a large number of voters of European descent had not forgiven Ford for his claim that there was no Soviet rule in Eastern Europe. After a skillful 22-month campaign across the country, Carter had been nominated on the first ballot as candidate for the US presidency at the New York Convention of the Democratic Party, selecting the “liberal” Senator from Minnesota as his vice-presidential candidate. WF Mondale. In the elections of November 2, 1976, thanks to the massive vote of the blacks, who had voted for the Democratic candidate in the proportion of four out of five, Carter won a narrow victory (51%) over his competitor GR Ford. In foreign policy, Carter’s campaign for “human rights” it has earned him sympathies among the progressive elements even outside the USA. In the Middle East, the American government came into conflict with the Israeli conservative government of M. Begin and M. Dayan, so that the mission of Foreign Minister CR Vance in 1977 did not yield appreciable results. The economic recovery also appears to be proceeding at a slower pace than expected.

Taking power on January 20, 1977, Carter immediately carried out an intense activity. In foreign policy, he intended to interpret “détente” by accompanying it with the defense of human rights, without however returning to the Cold War. In domestic politics, it sought to stimulate the economy and reduce unemployment without increasing inflation, with a national health plan, a federal energy plan, and a reform of the tax system as its long-range goals.

He began by granting forgiveness to those who opposed conscription for the Vietnam War. He then spoke out in favor of minimum wages and protective measures for miners. He was a supporter of the rapprochement with Cuba and the admission of the Republic of Vietnam to the UN (September 1977). It also initiated a gradual withdrawal of American troops from Korea and allowed visas to be granted to Communists wishing to visit the United States. He was also opposed to the introduction of new weapons of “marginal military value”. Personally opposed to abortion, he accepted the liberal opinion of the Supreme Court and opposed an amendment to the Constitution in support of the “right to life”. In February 1977, Carter sent Congress a budget that included expenses of $ 459 billion and revenues of $ 401 billion. He promised sweeping tax reforms and reorganization of government offices in the future, but those plans slowed down when his old friend Bert Lance, budget minister, was forced to resign over Congressional criticism of his easygoing personal financial maneuvers. To simultaneously cope with inflation, which was around 6% when he took office, and unemployment, which was around 8%, Carter would have preferred to rely on private stimuli. But, these proved insufficient, in August and September 1977 the government supported a bill that provided for government intervention. And in the October, the president signed a city aid bill totaling $ 14.7 billion. Carter was concerned about the multiplication of plutonium-producing nuclear reactors in both the USA and other countries. At the end of September 1977 SALT conversations with the Soviets resumed for the renewal of the treaty on the limitation of strategic weapons, which reached port in June 1979. The deposition of the Shah and the Islamic revolution in Iran marked a major American failure both strategically and for oil interests. Nor did the negative attitude of the USSR about compliance with the Helsinki agreements and the Soviet intransigence in matters of civil rights at the Belgrade Conference help. In the matter of the neutron bomb, Carter, after trying to persuade the allies to approve its construction, he ended up postponing its manufacture. Thanks to the president’s mediating ability, the Camp David accords took place in September 1978 which decided a separate peace between Egypt and Israel. The resumption of diplomatic relations with Beijing at the end of 1978 was also sensational, followed by the visit to the USA by Chinese Foreign Minister Deng Xsiaoping. Carter’s prestige, which decreased somewhat in 1979 especially as a result of economic policy, recovered after the events of Afghānistān (Soviet occupation, December 1979) and Iran (hostage-taking inside the American embassy in Tehran, November 1979; long diplomatic dispute over their release, winter 1979-80; application of economic sanctions toblitz by a marines commando to free the hostages (April 24-25, 1980); but his nomination in the presidential elections of November 1980 seems certain.